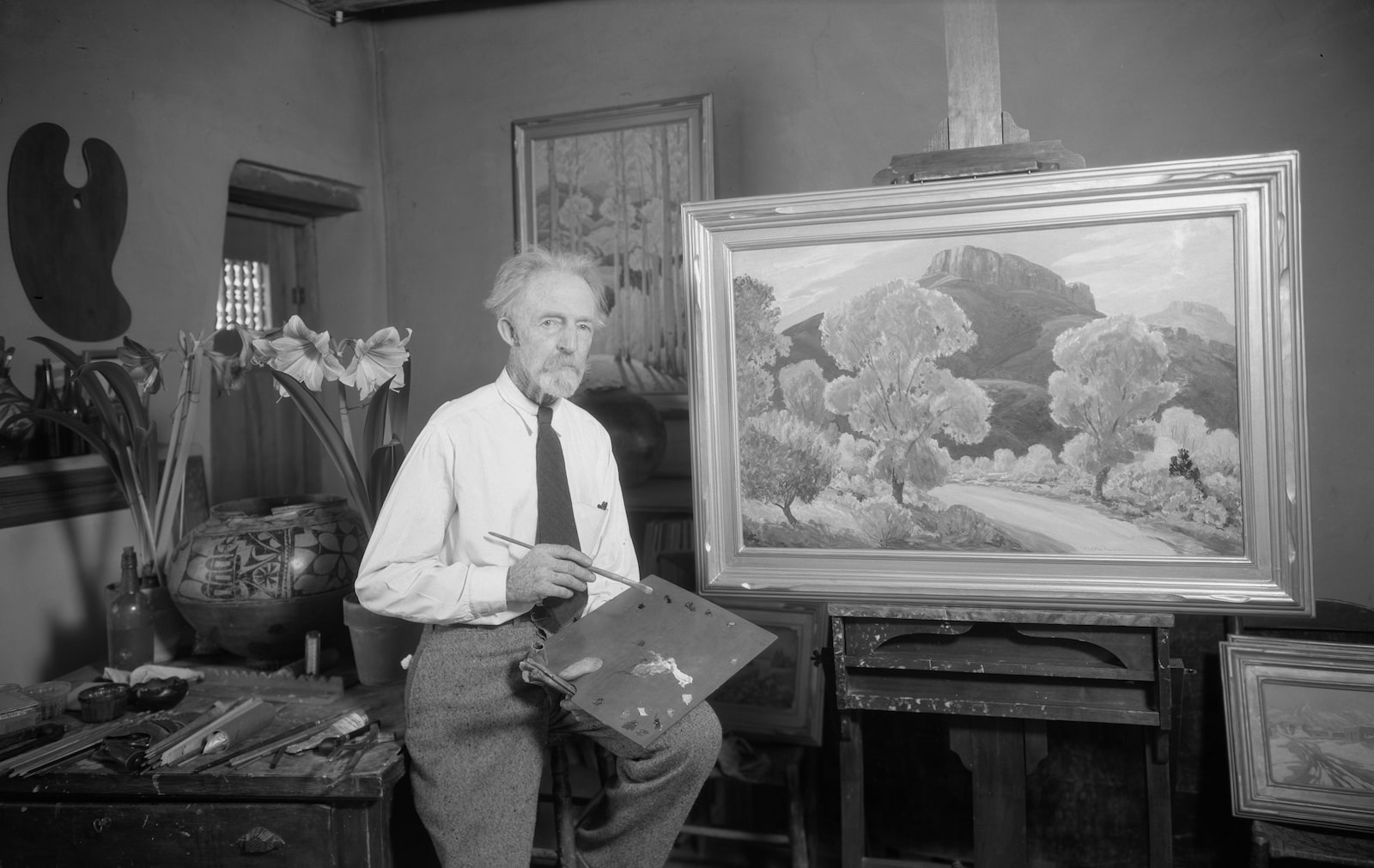

Harold (Hal) Edward West was born in Honey Grove, TX, and grew up in Mill Creek and Tishomingo, OK. Despite taking an early interest in drawing, he did not obtain much in the way of a formal art education. He took a few classes, one of which resulted in a prize for “best oil painting” at the county fair, and apprenticed at a commercial art studio in Dallas, TX, during or shortly after high school. He then went to work on the Mississippi River, eventually moving to Santa Fe, NM, in 1926, where he pursued a career in the arts.

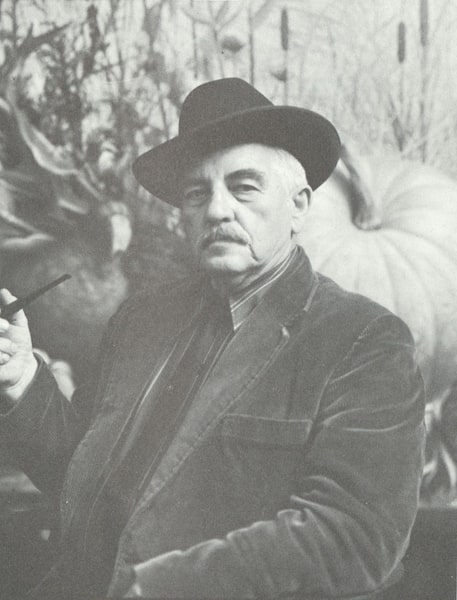

To start, West mostly worked as a commercial artist. Through the first half of the 1930s, he ran a business hand-printing textiles and calendars. He joined the New Deal in 1937 or 1938, mostly producing woodblock prints but also taking up oil painting again. He credits New Mexico’s Federal Art Project Director Russell Vernon Hunter as one of his mentors, and the New Deal as encouraging him to pursue a career in painting. In a 1964 interview, he referred to the New Deal as a “happy little period”: “It was a wonderful thing, and it helped me. I was still making a living . . . I stayed home and painted . . . They financed all the material, canvas and everything—brushes. And I got enthusiastic about painting and stayed with it.”1

While West would continue to take commercial art jobs (for example, designing the front cover for and illustrating Death in the Claimshack by John L. Sinclair), the New Deal brought him recognition within the realm of Western American art. He was given a solo show at the state art museum in 1938 and was selected as one of the artists to represent New Mexico at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, having developed a reputation as a self-taught artist uniquely adept at depicting frontier life—horses, cattle, and cowboys in particular. Echoing the sentiments of many of his contemporaries, Santa Fe New Mexican art critic Ben Krebs wrote of West in 1938 that “much of his life has been spent on ranches and his insight and understanding of ranch life and cowboy behavior is true.”2 Indeed, he lived on a 240-acre homestead south of Santa Fe with his wife and five children.

At the end of the New Deal and during WWII, from 1941 to 1945, West worked as a guard at the Santa Fe Internment Camp, a Japanese prison camp. During that time, he made a number of sketches of his fellow guards, which are now held by the Fray Angelico Library Archives.

West returned to painting professionally in 1945. In 1960, he opened a gallery at 601 Canyon Road in Santa Fe, and quickly became a fixture of the famous art district, known for straight talk and playing horseshoes (and poker). He created the “Guide to Canyon Road,” a directory of galleries on the street. West died at the age of sixty-six after a long illness.