Home » Special Exhibits » Views on the Southwest » Between Fact & Fiction

Views on the Southwest

Between Fact & Fiction

Artists as Storytellers

In addition to its unique landscapes, Western American artists were drawn to the Southwestern United States for its history and regional cultures. Fantasies of adventures on the range fueled some artists, while others turned their attention to Native American subjects.

Read More

The “Old West”—the wild adventures of rabble-rousing cowboys, suspenseful (and often violent) encounters between Native Americans and cowboys, and quieter moments on the range—is a major subject of Western American art that is present in Gallup’s New Deal art collection. Often inspired by nostalgia for a mythical West that had “passed” with the closing of the open range and relocation of most American Indian tribes to reservations, much of this imagery presents, somewhere between fact and fiction, a romanticized view of the region’s history.

Native American subjects—in portraits and scenes of everyday life—were considered both “exotic” and fundamentally and authentically “American” by many Anglo artists and their mostly urban patrons, some of whom had visited the Southwest and many who had not. Artists typically drew from academic training in Europe and the East Coast in conceiving of and constructing such paintings, but the images were also part of a larger visual culture of the tourism industry.

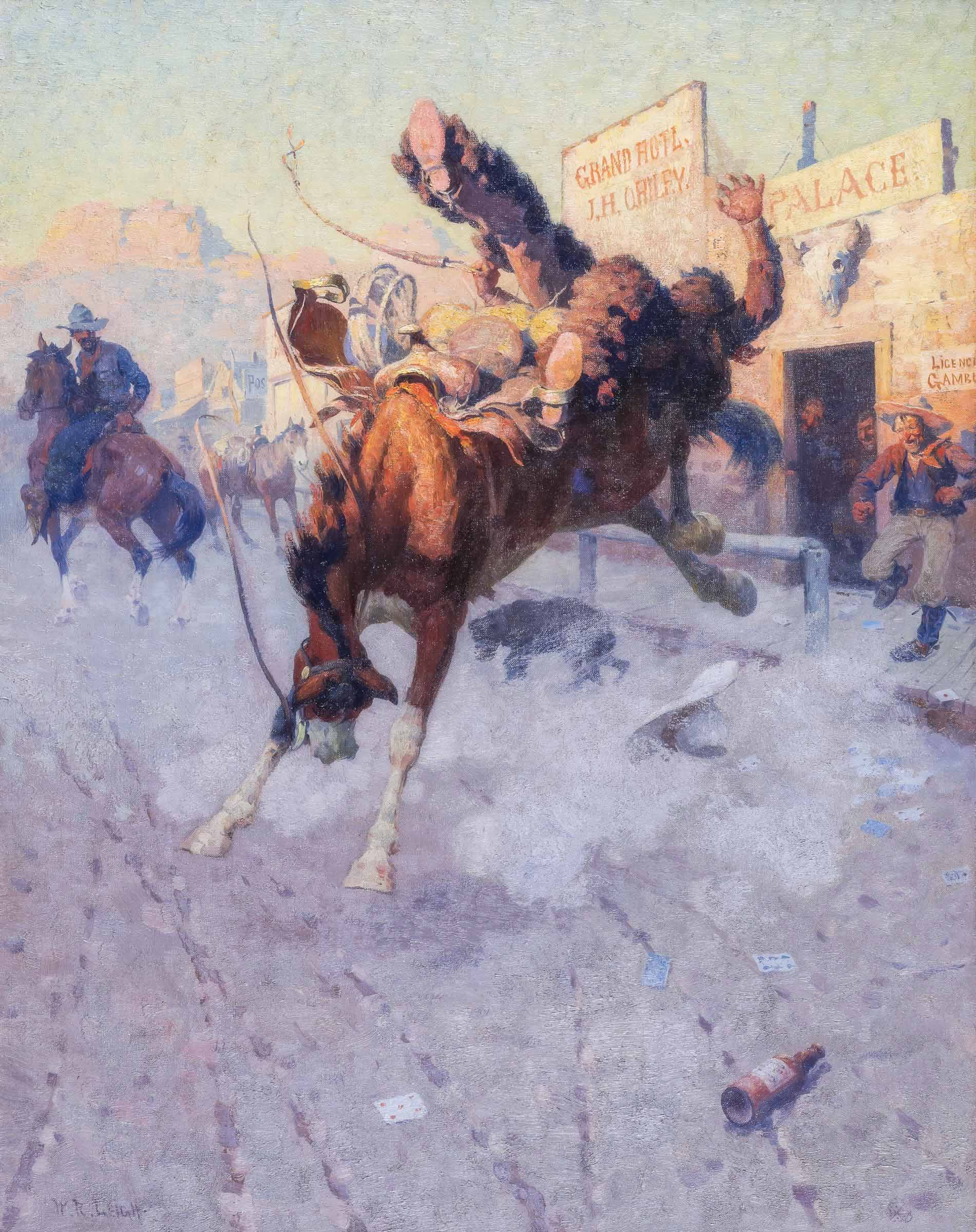

Western Adventure

This wild scene of a bucking bronco and precariously tipsy rider is unusual among Gallup’s Western American paintings. Of an earlier generation than most artists from the collection, William Robinson Leigh grew up in the era of dime novels that mythologized the Old West adventures of stereotypical “cowboys and Indians.” He realized his dream to experience the West firsthand in 1906, when he ventured to New Mexico from the East Coast on the Santa Fe Railroad. He returned dozens of times, taking his drawings back to his New York studio to use as source material for his dramatic paintings and illustrations.

Horses and Whiskey Don’t Mix is one of many of Leigh’s paintings that feature a wild tussle between horse and rider, with limbs flying and dust billowing. The story plays out even more through the details Leigh included around this swirling center of motion. Having established his career as a magazine illustrator, Leigh knew how to visually tell a story and stoke the viewer’s imagination through dramatic composition and details alike.

Hover your mouse over the painting to discover many easily overlooked details.

Look for

- scattered playing cards

- a discarded beer bottle

- a falling hat suspended in mid-air

- the Grand Hotel sign

- onlookers’ facial expressions

- a distant mesa

- a cowering dog

Where has the artist set the scene? What has happened before this moment? What will happen next?

Picturing Pueblo Life

The Art of Tourism

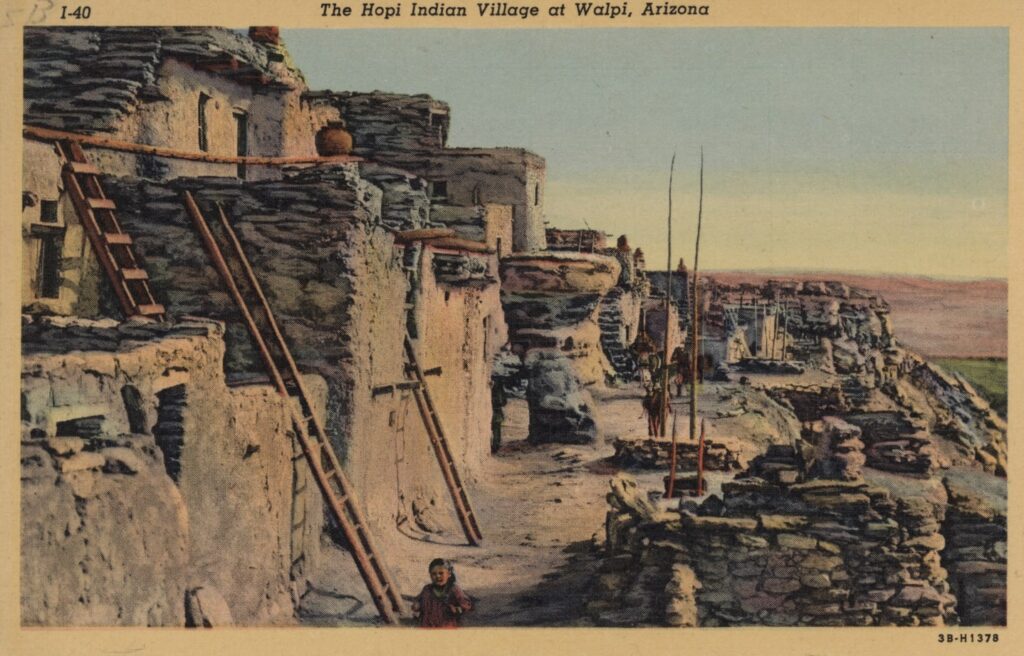

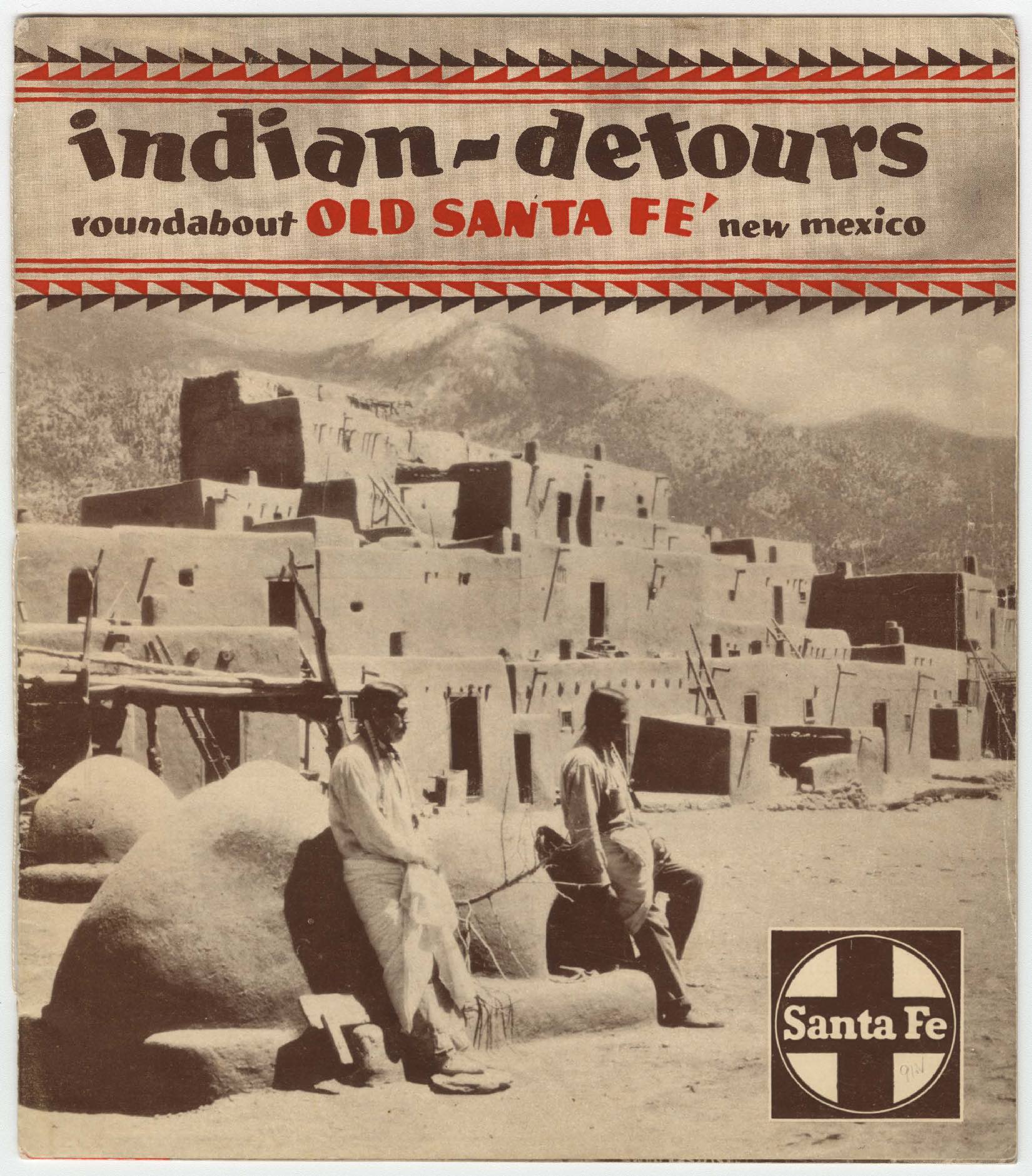

With the arrival of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway in New Mexico in the 1880s, tourism to the Southwest steadily increased in the half century that followed. Artists were an integral part of the advertising efforts to lure tourists to the region, painting breathtaking scenery and often romanticized vignettes of Indigenous people that were made available to the American public through prints, illustrated magazines, railway advertisements, and other forms of inexpensive, popular distribution. Imagery of “untouched” desert and canyon landscapes, unique adobe architecture and ancient ruins, and seemingly timeless Native people in rhythm with nature served to sell the Southwest to those seeking a change of scenery and a novel environment.

Once arrived at various depots in New Mexico or Arizona, rail passengers could embark on an “Indian Detour,” which offered a front-row view of Southwestern history and heritage. Launched in 1926 through a collaboration between the Santa Fe Railway and the Fred Harvey Company, which operated hotels, restaurants, and gift shops at railroad stations, Indian Detours took tourists “off the beaten path.” Tour guides transported visitors by car to remote areas and to Pueblo villages, where ceremonies adapted for public viewing were performed and tourists could take in a carefully constructed experience of Pueblo culture.

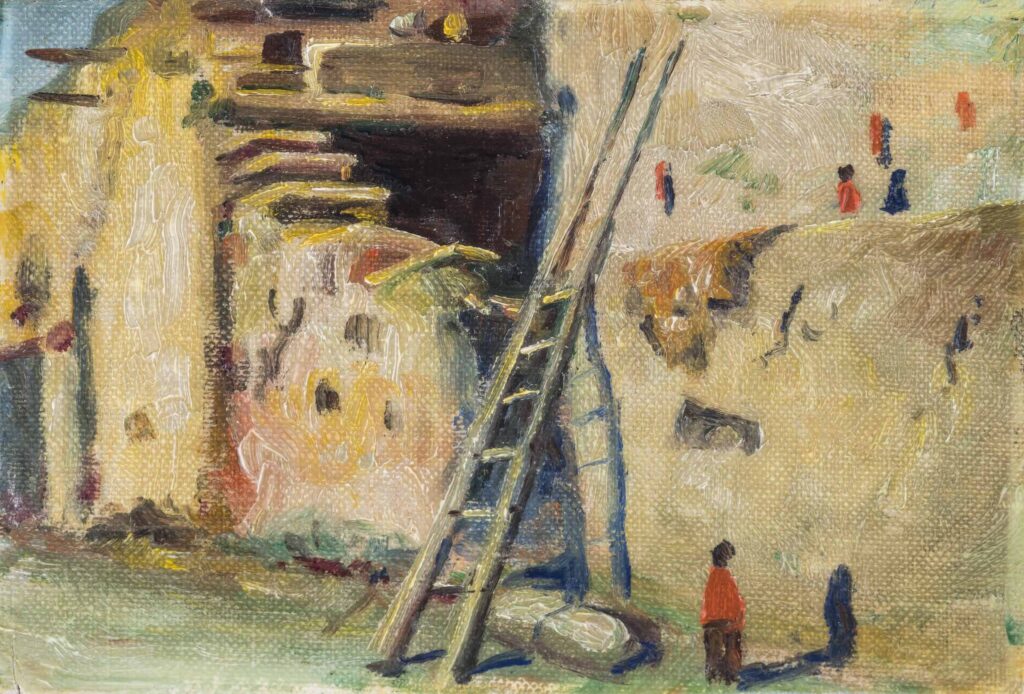

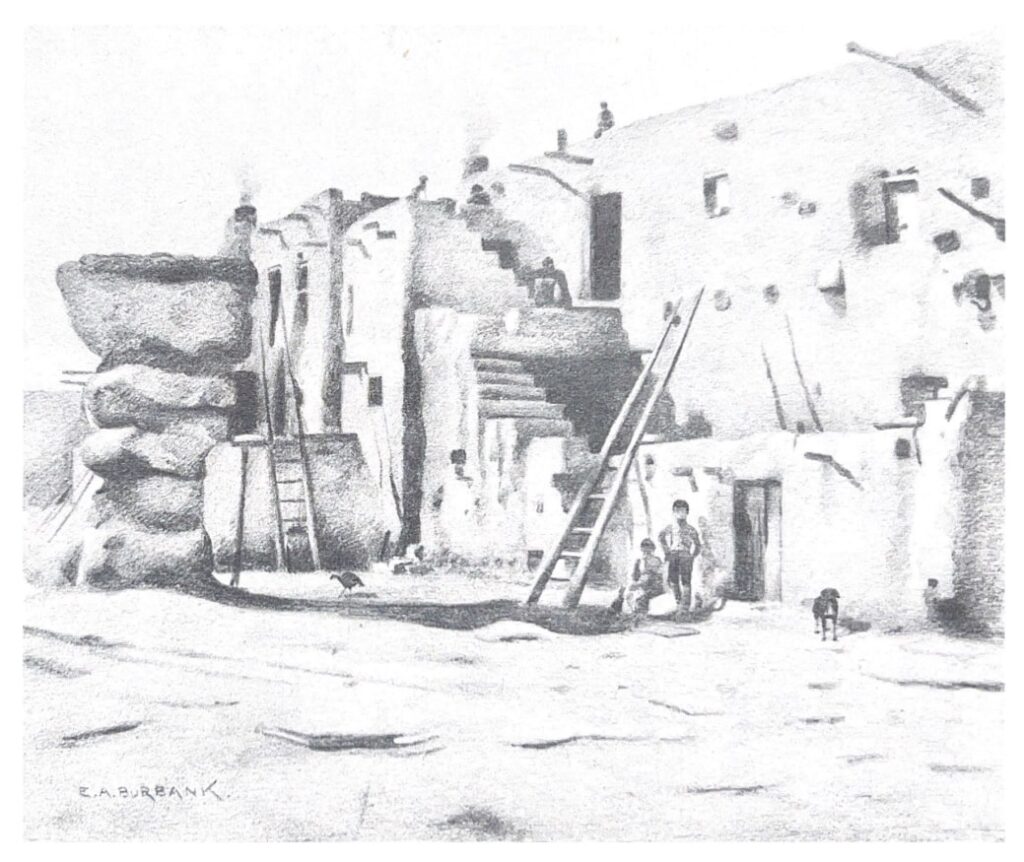

The Tourism of art

Paintings picturing Pueblo life, such as the two below, share similar imagery with the culture-based tourism industry. Like postcards and advertisements of the era, artists pictured everyday domestic activities, arts and handicrafts, and dances set against the Pueblo’s characteristic architecture, the vast Southwestern landscape, or a combination of the two. Although these vignettes gave the impression of a straightforward snapshot, they were often the result of methodical staging in the artist’s studio.

Click the arrow icon for each painting to learn more.

Where would you place these paintings on the scale below?

Native American Portraits

Historically, the role of portraiture in the American and European traditions has been to capture a sense of the sitter’s likeness, personality, identity, and status. Facial expressions, clothing, backdrops, and props aid in conveying these aspects of the subject. Albert Delmont Smith was a society portraitist in New York City who was particularly popular in the 1920s but later found success with commissions from the likes of President Dwight D. Eisenhower during his tenure as president of Columbia University (1948–53).

The context of Smith’s two portraits of Native American sitters in the Gallup New Deal art collections is unclear. How they made their way into the collection, who the sitters are, and why and for whom they were painted are all a mystery. They do, however, exist within and speak to a long history of Native American portraits created by Euro-American artists. In the 1800s, artists like George Catlin and Charles Bird King painted portraits in the spirit of documenting and “preserving” a “vanishing race,” as federal policies and westward settlement adversely impacted Native life and culture. By the turn of the century, photographer Edward Curtis cast a similarly ethnographic eye on Native American tribes and individual subjects. Taos Society artists, too, painted specific sitters alongside more generic, romanticized, portrait-like images of Native Americans.

For both paintings, Smith adapted principles of formal portraiture he had learned from his studies at the Art Students League in New York City. Both men are pictured half-length and at a three-quarter turn, allowing for a close visual cropping that emphasizes their clothing, accessories, facial features, and expressions. However, Smith’s representations of the men are a far cry from the East Coast society portraits for which he was known. A closer look at Chief Deer’s portrait reveals a magnificent but loose-fitting headdress and an oversized silver medallion reminiscent of those worn by Indian delegates in earlier eras. He gazes out into the distance, beyond the viewer, lips pensively sealed, a suggestion of time inscribed in the lines of his face and sagging jowls. The Half-Breed, which has suffered damage due to improper storage, pictures a younger man, slouching in ill-fitting clothing and casting a downward, withdrawn gaze.

It is unclear if the two paintings were created as a pair, but Smith most likely sent them as a set to Gallup.

As you look at them side by side, how do you read the juxtaposition between old and young, chief and “half-breed” (a derogatory term for a biracial Native American person)? What other artistic choices further emphasize each sitter’s identity (or stereotype)?